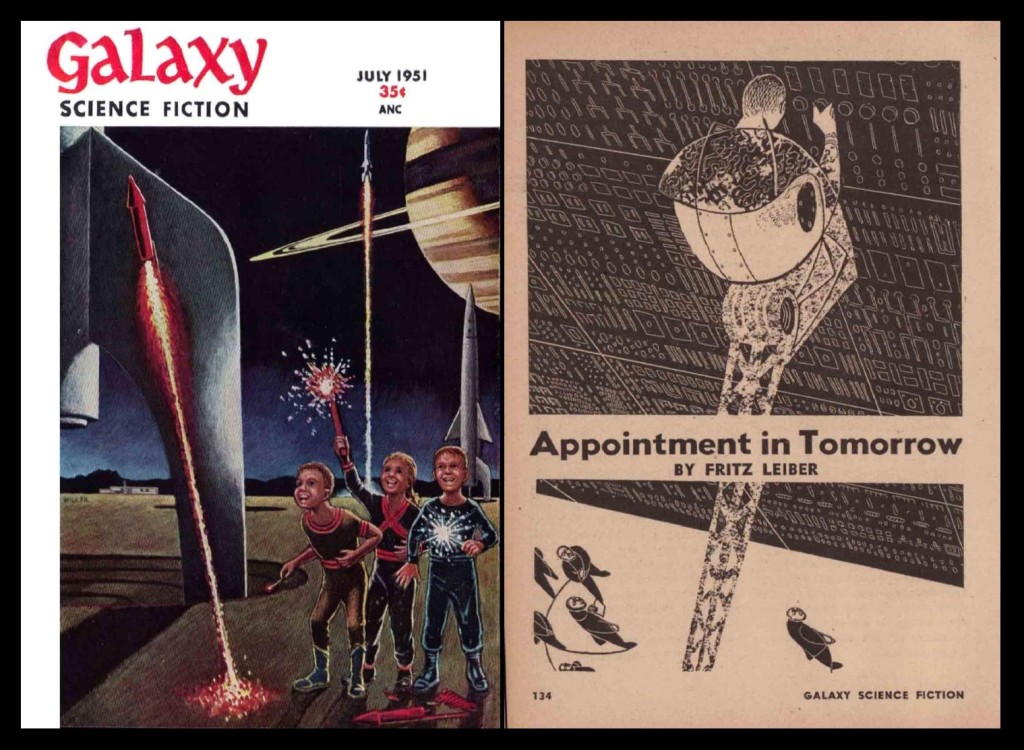

“Poor Superman” by Fritz Leiber is story #34 of 52 from The World Treasury of Science Fiction edited by David G. Hartwell (1989), an anthology my short story club is group reading. Stories are discussed on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. “Poor Superman” was initially titled “Appointment in Tomorrow” and published in Galaxy Science Fiction (July 1951). It was reprinted and retitled in the 1952 anthology hardback Tomorrow the Stars edited by Robert A. Heinlein. You can read the story online at Project Gutenberg. You can listen to a radio show adaption of “Appointment in Tomorrow” from X Minus One. You can find ebook editions here to download.

I will refer to the story as “Poor Superman” instead of its original title “Appointment in Tomorrow.”

I read “Poor Superman” years ago when I read The Best Science Fiction Stories: 1952 edited by Everett F. Bleiler and T. E. Dikty. I didn’t remember anything from then when I read it again yesterday, on Friday. After that second reading, I had a vague feeling of reading it before and thinking it a so-so story. But this time I thought there was more there, but found the story confusing to read. I started thinking about it. Then today, Saturday, I read it again, and it all clicked. I would have said on my first reading I would have given the story 3 stars. On the second reading, I realized it was approaching 4 stars. On my third reading, it’s a 5-star story. I believe I needed to know what was in the story before I could understand reading each line of the story. Now it works word by word, line by line.

Fritz Leiber’s story, “Coming Attraction” is one of my all-time favorite science fiction short stories. It appeared a year earlier than “Poor Superman” in Galaxy. David Hartwell in his introduction suggests that they are both set in the same fictional post-WWIII universe, but I thought “Poor Supermen” only hinted at a few of the ideas from the earlier story.

Unfortunately, where “Coming Attraction” was dazzling, vivid, and dramatic on first reading, “Poor Superman” was talky, full of infodumps, and somewhat confusing on first reading. My second reading was really like another first reading. However, on this second reading, I sensed it was a far more ambitious story. “Coming Attraction” is about a British man meeting a woman in New York City in post-atomic war WWIII. It’s about a personal conflict between two men and a woman. “Poor Superman” involves a power struggle at the top of society between the Thinkers, who currently influence the party in the Whitehouse, and scientists who wish to unmask the frauds the Thinkers are perpetrating to maintain that political power.

It took a third reading to get who was who, all the implications, and to understand the reasons for all the infodumps. “Poor Superman” is an attack on science fiction, science fiction fans, as well as other kinds of believers, including religious, political, and philosophical. It’s more than cynical, it’s harshly realistic. You might think that Lieber supports science and scientists, but he’s brutal on them too.

Now “Poor Superman” needs a lot of setting up to really appreciate. It helps to know what was going on at Astounding Science Fiction magazine, where the editor John W. Campbell, and many of his writers were promoting the pseudo-science Dianetics. Many science fiction writers and readers from the 1940s believed that mankind was about to discover vast psychic powers that would change the world. Leiber doubts this.

Here’s how Leiber described his post-WWIII America of this story:

It was America approaching the end of the Twentieth Century. America of juke-box burlesque and your local radiation hospital. America of the mask-fad for women and Mystic Christianity. America of the off-the-bosom dress and the New Blue Laws. America of the Endless War and the loyalty detector. America of marvelous Maizie and the monthly rocket to Mars. America of the Thinkers and (a few remembered) the Institute. "Knock on titanium," "Whadya do for black-outs," "Please, lover, don't think when I'm around," America, as combat-shocked and crippled as the rest of the bomb-shattered planet.

In the real world of 1951, the cold war was heating up, now with two superpowers with atomic bombs, both of which were racing to develop a thermonuclear weapon. The United States was consumed by anti-communist fervor, with the HUAC witchhunts well underway. Americans were paranoid and frightened — grasping at religion, the occult, UFOs, ESP, faith healing, science fiction, and other forms of quackery. Many science fiction stories during these years were written about civil wars fought by the faithful against scientists. Heinlein was predicting his “Crazy Years” stories in his Future History series. Andre Norton would soon publish The Stars Are Ours! about scientists being hunted down after a theocracy takes over America. Leigh Brackett would publish The Long Tomorrow in 1955, about America reverting to an Amish-like society.

I wish Leiber hadn’t named his Dianetics-driven characters Thinkers. It’s too easy to confuse them with the Scientists, whom most people think of as big thinkers. I wished he had called them the Psychics, Mentalists, or something closer to what they represented. It’s a shame he couldn’t have called them The Scientologists – I don’t think they were using that name yet in 1951, but that label perfectly describes his characters. What would you think about reading “Poor Superman” today if he had written a story about Scientists versus Scientologists?

In “Poor Superman” the Thinkers believe they are developing powerful mental abilities. Americans believe that Thinkers are superior, and they influence political power. The Thinkers maintain the public belief in their superiority by claiming to have a giant two-floor-sized supercomputer that can answer all questions, and by faking space missions to Mars where they claim spiritually advanced Martians with ESP powers are teaching them their secrets which they will soon give to everyone.

This is a great setup for a story. The Galaxy editors introduced it with two questions: “Is it possible to have a world without moral values? Or does lack of morality become a moral value, also?” Think about those two questions. They are perfect for asking ourselves in 2023. It’s possible to substitute Donald Trump and his MAGA followers for the Thinkers in “Poor Superman.” If you do, it might make you admire “Poor Superman” more. And anyone reading or rereading Stranger in a Strange Land should get to know “Poor Superman” first.

The trouble is, I found “Poor Superman” confusing to read at first. Of course, this might be entirely my fault. There were too many weird made-up names that I couldn’t keep up with. I kept forgetting which character belong to which group. And there were times I just didn’t get the scene. It wasn’t until my third reading that “Poor Superman” became crystal clear like “Coming Attraction.”

An example of confusion from Friday’s reading is when they give questions to the supercomputer, Maize.

From a new Whitehouse, the President and his general staff observe while the daily questions are submitted to Maize, in what I assume is broadcast to Americans too. Instead of typing the questions, the questions are entered by taping. My guess is Leiber meant to imply writing in the future is done on spools of magnetic tape. But that’s only a guess. Then we are told:

Meanwhile the question tape, like a New Year's streamer tossed out a high window into the night, sped on its dark way along spinning rollers. Curling with an intricate aimlessness curiously like that of such a streamer, it tantalized the silvery fingers of a thousand relays, saucily evaded the glances of ten thousand electric eyes, impishly darted down a narrow black alleyway of memory banks, and, reaching the center of the cube, suddenly emerged into a small room where a suave fat man in shorts sat drinking beer. He flipped the tape over to him with practiced finger, eyeing it as a stockbroker might have studied a ticker tape. He read the first question, closed his eyes and frowned for five seconds. Then with the staccato self-confidence of a hack writer, he began to tape out the answer. For many minutes the only sounds were the rustle of the paper ribbon and the click of the taper, except for the seconds the fat man took to close his eyes, or to drink or pour beer. Once, too, he lifted a phone, asked a concise question, waited half a minute, listened to an answer, then went back to the grind. Until he came to Section Five, Question Four. That time he did his thinking with his eyes open. The question was: "Does Maizie stand for Maelzel?" He sat for a while slowly scratching his thigh. His loose, persuasive lips tightened, without closing, into the shape of a snarl. Suddenly he began to tape again. "Maizie does not stand for Maelzel. Maizie stands for amazing, humorously given the form of a girl's name. Section Six, Answer One: The mid-term election viewcasts should be spaced as follows...." But his lips didn't lose the shape of a snarl.

What I didn’t realize on my first reading today was the fat man in shorts was answering the questions for Maize. It’s obvious when I reread it, but it wasn’t on first reading. I thought he was a computer operator that retyped the questions into the computer. What we learn from this is the Thinkers are faking they have a supercomputer.

We also learn they are faking missions to Mars. An astronaut and his cat go up and just orbit the Earth while biding time. He pretends to have gone to Mars.

A scorecard of the characters:

- Jorj Helmuth – Thinker (40 years old, with a body of 20, and a mind of 60)

- President of the U.S. and staff – unnamed

- Maizie – supercomputer AI (faked)

- Morton Opperly – wise old physicist

- Williard Farquar – young ambitious physicist

- Jan Tregarron – fat man in loud shorts who is the mastermind of the Thinkers

- Miss Arkady “Caddy” Simms – seductress, spy, femme fatale

In a conversation between Morton Opperly and Williard Farquar, we learn something about the conflict between Thinkers and Scientists:

"But what are we to do?" Farquar demanded. "Surrender the world to charlatans without a struggle?" Opperly mused for a while. "I don't know what the world needs now. Everyone knows Newton as the great scientist. Few remember that he spent half his life muddling with alchemy, looking for the philosopher's stone. Which Newton did the world need then?" "Now you are justifying the Thinkers!" "No, I leave that to history." "And history consists of the actions of men," Farquar concluded. "I intend to act. The Thinkers are vulnerable, their power fantastically precarious. What's it based on? A few lucky guesses. Faith-healing. Some science hocus-pocus, on the level of those juke-box burlesque acts between the strips. Dubious mental comfort given to a few nerve-torn neurotics in the Inner Cabinet—and their wives. The fact that the Thinkers' clever stage-managing won the President a doubtful election. The erroneous belief that the Soviets pulled out of Iraq and Iran because of the Thinkers' Mind Bomb threat. A brain-machine that's just a cover for Jan Tregarron's guesswork. Oh, yes, and that hogwash of 'Martian wisdom.' All of it mere bluff! A few pushes at the right times and points are all that are needed—and the Thinkers know it! I'll bet they're terrified already, and will be more so when they find that we're gunning for them. Eventually they'll be making overtures to us, turning to us for help. You wait and see." "I am thinking again of Hitler," Opperly interposed quietly. "On his first half dozen big steps, he had nothing but bluff. His generals were against him. They knew they were in a cardboard fort. Yet he won every battle, until the last. Moreover," he pressed on, cutting Farquar short, "the power of the Thinkers isn't based on what they've got, but on what the world hasn't got—peace, honor, a good conscience...."

But what appeals to me, is Fritz Leiber’s take on science fiction and science fiction fans. Over the past couple of years, as I’ve been reading, and rereading 1950s science fiction, I keep getting hints that some science fiction writers were developing cynical attitudes towards the genre. At one point, Jorj Helmuth thinks to himself:

He switched out all the lights and slumped forward, blinking his eyes and trying to swallow the lump in his throat. In the dark his memory went seeping back, back, to the day when his math teacher had told him, very superciliously, that the marvelous fantasies he loved to read and hoarded by his bed weren't real science at all, but just a kind of lurid pretense. He had so wanted to be a scientist, and the teacher's contempt had cast a damper on his ambition.

Then in a desperate speech to Jan Tregarron, Jorj Helmuth explains why he created the Thinkers:

"Our basic idea was that the time had come to apply science to the life of man on a large scale, to live rationally and realistically. The only things holding the world back from this all-important step were the ignorance, superstition, and inertia of the average man, and the stuffiness and lack of enterprise of the academic scientists— their worship of facts, even when facts were clearly dangerous." "Yet we knew that in their deepest hearts the average man and the professionals were both on our side. They wanted the new world visualized by science. They wanted the simplifications and conveniences, the glorious adventures of the human mind and body. They wanted the trips to Mars and into the depths of the human psyche, they wanted the robots and the thinking machines. All they lacked was the nerve to take the first big step— and that was what we supplied."

You can see L. Ron Hubbard here. You can see John W. Campell. And maybe even some Robert A. Heinlein.

There’s a reason why the story was retitled “Poor Superman.” And there’s a good reason why H. L. Gold didn’t want to use that title. Any science fiction fan would understand what it meant in 1951.

I need to read “Poor Superman” again. The ending is not ambiguous, but I wonder if it shouldn’t be. Poor Superman turns out to be Jorj Helmuth because Caddy puts the gun in Jan Tregarron’s hand. But if we weren’t told that one bit of information, and we only knew Caddy had the gun, who would have been Poor Superman? Jan or Jorg? Jan acts like a Nazi, and they thought of themselves as supermen too.

This is a great story. It just took three readings to discover that. I wonder what more readings will reveal. I need to read more stories by Fritz Leiber, especially more of his work from the 1950s.

James Wallace Harris, 7/22/23

If you want to read more ’50s Leiber, don’t miss “The Foxholes of Mars,” which shares a lot attitudinally, if in no other way, with “Coming Attraction.” It’s readily available both in the fine old collection A PAIL OF AIR and in the Ballantine/SFBC THE BEST OF FRITZ LEIBER, among other places.

LikeLike