Reading the Pulps 7: “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany

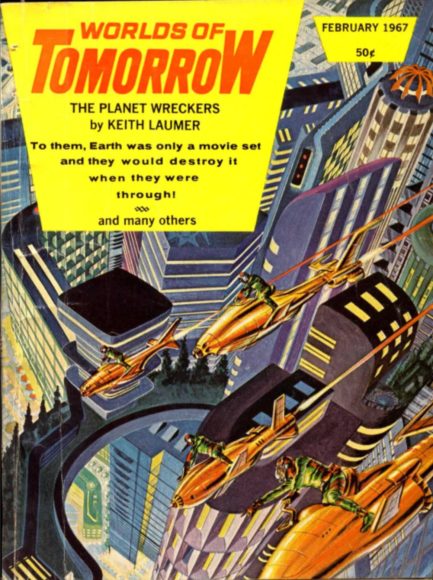

“The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany first appeared in Worlds of Tomorrow February 1967.

You might already own “The Star Pit” in one of these books:

- SF 12 edited by Judith Merril

- Driftglass by Samuel R. Delany

- The Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels edited by Robert Silverberg and Martin H. Greenberg

- Modern Classic Short Novels of Science Fiction edited by Gardner Dozois (only U.S. ebook edition of this story I know about.)

- Aye, and Gomorrah by Samuel R. Delany (Delany’s current short story collection that’s still in print.)

Warning: This column contains spoilers.

“The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany is a complex novella I’ve read several times in the last half-century. It reiterates common themes Delany dwelt on in the 1960s as a young writer. “The Star Pit” explores the emotions we feel when we discover places we can’t go but other people can. The story analyzes how dissatisfaction of not fitting in makes us want to go elsewhere.

I related to this story strongly back in 1967 because of the anguish I felt wanting to be an astronaut and learning I couldn’t. I didn’t have 20-20 vision. I didn’t understand back then why I wanted to leave the Earth. In the decades since I’ve learned that there are countless existential locations I can’t go, that others can. I’ve since learned why I was unhappy wherever I was, making this story more beautiful every time I reread it. Anyone who reads “The Star Pit” will discover analogies with their own dissatisfactions and limitations.

Have I been a life-long science fiction fan because I couldn’t go into space? I’m not part of the Millennium Falcon generation, where science fiction is pure escapist fantasy. My favorite spacecraft has always been the Gemini space capsule, something that was as down-to-Earth as a Volkswagon Beetle. My astronaut ambitions began with reading Have Space Suit – Will Travel and ended with “The Star Pit,” a period that coincided with the duration of Project Gemini in the 1960s. Of course, I didn’t know besides poor vision I completely lacked the right stuff until I encountered Tom Wolfe’s book.

Over the years I’ve read many astronaut memoirs and they’ve all taught me the same thing: I’m an earthling. Reading “The Star Pit” shows us the boundaries of our ecological existence. It reveals the dissatisfaction of not fitting in pushes us to leave, and at some point, we butt into a barrier like a guppy in an aquarium.

I’ve always read science fiction because I thought it prepared us for the future. I believed being a science fiction fan supported colonizing the solar system. Now I have doubts. What if humans can’t spread across moons, planets, and the galaxy? Is “The Star Pit” an analogy for that too?

Like Kip Russell in the Heinlein novel, I fantasized in 1967 I’d find a way into space one way or another. I was desperate to get to Mars. I didn’t really know why then. I probably assumed my religion, science fiction, demanded it. As I got older I discovered all the ways I couldn’t adjust to my environment. Was a lifetime of reading science fiction my Zoloft to ease the anxiety of never fitting in and never escaping? Or was the vicarious thrill of science fiction all I ever really needed, like a drug? Wisdom has taught me I never could have been an astronaut. I now know I would hate living in space. So, why do I still read science fiction? That answer also lies in “The Star Pit.” Delany’s words weave the allure of living on other worlds. “The Star Pit” is also an ecologarium.

Is fiction our substitute for living lives of quiet desperation? Some people want to do things in life so badly that they make it happen. Or, die trying. As a kid, I thought anything was possible, and I’d be one of those people who’d overcome all odds. I wasn’t. I just didn’t know that in 1967.

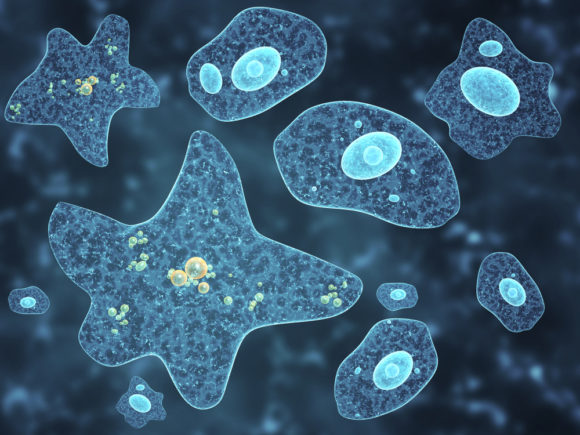

I have a thought experiment I sometimes use to see my life more clearly. I call it the Amoeba Analogy or The Microscope Perspective. Have you ever studied pond water under the microscope and watched simple multicellular animals go through their interactions? Imagine seeing your own life from above, as through a microscope lens. It’s a great way to visualize the finite limitations of our own ecologarium.

Delany starts his story with a description of an ecologarium, a reoccurring analogy in this story:

Two glass panes with dirt between and little tunnels from cell to cell: when I was a kid I had an ant colony.

But once some of our four-to-six-year-olds built an ecologarium with six-foot plastic panels and grooved aluminum bars to hold corners and top down. They put it out on the sand.

There was a mud puddle against one wall so you could see what was going on underwater. Sometimes segment worms crawling through the reddish earth hit the side so their tunnels were visible for a few inches. In hot weather the inside of the plastic got coated with mist and droplets. The small round leaves on the litmus vines changed from blue to pink, blue to pink as clouds coursed the sky and the pH of the photosensitive soil shifted slightly.

The kids would run out before dawn and belly down naked in the cool sand with their chins on the backs of their hands and stare in the half-dark till the red mill wheel of Sigma lifted over the bloody sea. The sand was maroon then, and the flowers of the crystal plants looked like rubies in the dim light of the giant sun. Up the beach the jungle would begin to whisper while somewhere an ani-wort would start warbling. The kids would giggle and poke each other and crowd closer.

Then Sigma-prime, the second member of the binary, would flare like thermite on the water, and crimson clouds would bleach from coral, through peach, to foam. The kids, half on top of each other now, lay like a pile of copper ingots with sun streaks in their hair—even on little Antoni, my oldest, whose hair was black and curly like bubbling oil (like his mother’s), the down on the small of his two-year-old back was a white haze across the copper if you looked that close to see.

More children came to squat and lean on their knees, or kneel with their noses an inch from the walls, to watch, like young magicians, as things were born, grew, matured, and other things were born. Enchanted at their own construction, they stared at the miracles in their live museum.

A small, red seed lay camouflaged in the silt by the lake/puddle. One evening as white Sigma-prime left the sky violet, it broke open into a brown larva as long and of the same color as the first joint of Antoni’s thumb. It flipped and swirled in the mud a couple of days, then crawled to the first branch of the nearest crystal plant to hang exhausted, head down, from the tip. The brown flesh hardened, thickened, grew black, shiny. Then one morning the children saw the onyx chrysalis crack, and by second dawn there was an emerald-eyed flying lizard buzzing at the plastic panels. “

Oh, look, Da!” they called to me. “It’s trying to get out!”

Samuel Delany was an active organism himself back in the 1960s. He traveled far and wide. “The Star Pit” is a story about people like him who wanted to go further and do more but couldn’t. Before I read this story, I wanted to be like Wally Schirra and fly in the Gemini space capsule. In “The Star Pit” we meet a kid who wants to be Golden and travel to other galaxies.

Delany uses my Amoeba Analogy with his ecologarium, reminding readers we are part of an ecology. The structure of “The Star Pit” is like Russian Matryoshka nesting dolls. Delany loves recursive or circular plots, the most famous of which is used in Empire Star.

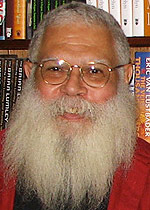

Vyme, age 42, is the largest of the nesting dolls, and our protagonist. Vyme is a black man, which was uncommon back then in science fiction. I didn’t know it at the time, but Delany was black and gay. Delany was only in his twenties when he wrote this story, so I imagine he was projecting himself as an older man in Vyme. Vyme is a drunk, and failed father. My own father was an alcoholic and failed dad too, which is another personal reason why I relate to this story. The main events in “The Star Pit” take place years after the beautiful introduction above. The Star Pit is an artificial world where intergalactic travelers come and go at the edge of the galaxy. Vyme owns a garage for spaceships and helps wayward kids get work to atone for abandoning his own children.

In Delany’s fictional universe, most humans go crazy if they get twenty-thousand light years beyond the galaxy’s edge, and die at twenty-five thousand. Only a few humans have the psychological make-up to travel across the void between galaxies. They are called Golden. This is the analogy with the average citizen of the 1960s and astronauts, but for many other things too. This story contains Ptolemaic circles within circles of analogies.

Another nesting doll in this story is Ratlit, a thirteen-year-old precocious kid who has already published a novel. Vyme sees Ratlit in himself, and we also know that Delany was a precocious kid who wrote a novel too. Ratlit hates the Golden because he wants to travel to other galaxies (Delany’s metaphor for racism?). Ratlit is in love with Alegra, a girl born with psychic powers and an addiction to an exotic drug from another galaxy. She’s a couple years older than Ratlit, and he uses her to view the worlds on distant galaxies because she can project imagery from the minds of the Golden.

Between the ages of Ratlit and Vyme is Sandy, another man who fails at marriage. Marriages in “The Star Pit” are complex group affairs, so Vyme and Sandy fail to fit into their societies. They are loners. Sandy also sees Ratlit as a younger version of himself and realizes Ratlit will eventually hurt Vyme and tries to protect him. Vyme and Sandy witness two Golden fight, with one killing the other. The victor gives the dead Golden’s spaceship to Sandy and Vyme. Ratlit wants them to give him the spaceship so he can give it to a Golden that’s come between him and Alegra.

Vyme wants to help Ratlit, and Sandy wants to protect Vyme. Each of them knows they are trapped by limitations, each of them tries to help the other get beyond those limits. Vyme, Sandy, and Ratlit each feel they are the most wisely experienced despite their ages. I assume Delany sees these three characters as himself at different ages. And I’m not sure if all the characters aren’t Delany in some ways, even the mean and dumb Golden.

The last doll in the nesting is An, for Androcles, a Golden. He has another ecologarium, this one a small sphere he wears around his neck, with a tiny microscope built onto it. He lets Vyme look at it:

I looked through the brass eyepiece.

I’d swear there were over a hundred life forms with a five to fifty stages each: spores, zygotes, seeds, eggs, growing and developing through larvae, pupae, buds, reproducing through sex, syzygy, fission. And the whole ecological cycle took about two minutes.

Spongy masses like red lotuses clung to the air bubble. Every few seconds one would expel a cloud of black things like wrinkled bits of carbon paper into the gas where they were attacked by tiny motes I could hardly see even with the lens. Black became silver. It fell back to the liquid like globules of mercury, and coursed toward the jelly that was emitting a froth of bubbles. Something in the froth made the silver beads reverse direction. They reddened, sent out threads and alveoli, until they reached the main bubble again as lotuses.

The reason the lotuses didn’t crowd each other out was because every eight or nine seconds a swarm of green paramecia devoured most of them. I couldn’t tell where they came from; I never saw one of them split or get eaten, but they must have had something to do with the thorn-balls—if only because there were either thorn-balls or paramecia floating in the liquid, but never both at once.

A black spore in the jelly wiggled, then burst the surface as a white worm. Exhausted, it laid a couple of eggs, rested until it developed fins and a tail, then swam to the bubble where it laid more eggs among the lotuses. Its fins grew larger, its tail shriveled, splotches of orange and blue appeared, till it took off like a weird butterfly to sail around the inside of the bubble. The motes that silvered the black offspring of the lotus must have eaten the parti-colored fan because it just grew thinner and frailer till it disappeared. The eggs by the lotus would hatch into bloated fish forms that swam back through the froth to vomit a glob of jelly on the mass at the bottom, then collapse. The first eggs didn’t do much except turn into black spores when they were covered with enough jelly.

All this was going on amidst a kaleidoscope of frail, wilting flowers and blooming jeweled webs, vines and worms, warts and jellyfish, symbiotes and saprophytes, while rainbow herds of algae careened back and forth like glittering confetti. One rough-rinded galoot, so big you could see him without the eyepiece, squatted on the wall, feeding on jelly, batting his eye-spots while the tide surged through quivering tears of gills.

I blinked as I took it from my eye.

“That looks complicated.” I handed it back to him.

“Not really.” He slipped it around his neck. “Took me two weeks with a notebook to get the whole thing figured out. You saw the big fellow?”

“The one who winked?”

“Yes. Its reproductive cycle is about two hours, which trips you up at first. Everything else goes so fast. But once you see him mate with the thing that looks like a spider web with sequiris—same creature, different sex—and watch the offspring aggregate into paramecia, then dissolve again, the whole thing falls into—”

“One creature!” I said. “The whole thing is a single creature!”

In many, if not all of Delany’s stories in the 1960s, he gives us characters who anguish over their limitations and resent people who have already done things they hope to do. His characters often feel their cherished uniqueness challenged when they meet others who mirror their talents. Ultimately, even the Golden have limitations. They discover lifeforms that can travel between universes. The lesson of this tale is no matter how far you can go, there are always others who can go further, and there are always further places to go.

When I read “The Star Pit” in 1967 I suffered because I couldn’t go into space. Delany was a black gay man who couldn’t go places in my white world where I could. The funny thing is, there were endless exotic places on Earth we both could have gone that were just as far out as anything he wrote or I read in science fiction.

Science fiction today is consumed as a kind of virtual reality for enjoying space travel fantasies. I still read hard science fiction stories where SF writers try to imagine how colonizing space is possible, but they are less common. Why do we want to leave Earth? Are we dissatisfied with life here? Or do we need to go further, to places we currently can’t go?

Is a Sci-Fi fan’s desire to live in outer space any different from a Christian’s desire to dwell in heaven? Or any more realistic? Aren’t most of the places we anguish over not being able to reach also not real anyway? Aren’t we all rejecting an acutely real life on Earth? Isn’t the ultimate point of this story to teach us how stay and coexist in our own ecologarium?

JWH

Stories for Chip: Fellow Writers Salute Samuel R. Delany

Stories for Chip is a collection of fiction and essays in honor of Samuel R. Delany. Two ways of approaching this review suggest themselves.

Stories for Chip is a collection of fiction and essays in honor of Samuel R. Delany. Two ways of approaching this review suggest themselves.

1. Since I have read only two Delany novels and would place neither on my favorite list, I could humbly remove myself from making further comment.

2. I could consider my relative lack of first hand experience of Delany’s work as a plus when it comes to considering the stories anthologized here strictly on their own merits.

Obviously I am going to go with the second option, but I need to say something more about the first.

I read Nova and The Einstein Intersection about four years ago. Nova I didn’t particularly like for reasons I no longer clearly remember. Einstein entertained and intrigued me, although I remember not quite “getting” the end. Looking at other reader reviews, I saw that I was not alone in that response. Looking recently at a range of reader reviews I see that Delany can be a polarizing author. Encomia are balanced out by disparaging comments from those who find the work opaque or over-written. This is especially true when it comes to Delany’s big books, Dahlgren and Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand. In one of his letters, Philip K. Dick, an author I think very highly of, reports throwing his copy of Dahlgren across the room before he was a hundred pages into it. In some cases, readers are put off by Delany’s content. These negative, sometimes angry responses, combined with what I’ve read in this new book, have actually renewed my interest in going back to Delany.

I have also read a third Delany novel. When I was in the book business, a small gay publishing house needed to remainder a few hundred copies of Hogg, one of Delany’s forays into pornography. I bought them and sold them for between $10 and $50 as their number decreased. I also read it. I can’t take the time to be shocked, but it is a variety of violent, transgressive pornography that leaves me puzzled about both its purpose and its audience. But a recent edition of the Los Angeles Review of Books ran an article on Hogg, “Uses of Displeasure: Literary Value and Affective Disgust,” by Liz Janssen. Again, the jury is split.

Stories for Chip is not a collection of pastiches. The writers have apparently been chosen because they work under Delany’s influence and address his themes. I have to say “apparently” because the book comes with essentially no editorial content, and it is badly needed. This situation was worsened by the advance ebook I received from Net Galley. The Table of Contents listed a Contributors page, but it was nowhere to be found. And the transcription was the worst I have ever encountered. Words were run together, sometimesuptotheextentofanentire sentence. A couple of stories with particularly dense or playful language were unreadable.

There is a lot of very good stuff here, and even the absence of the Contributors section worked to my advantage. I knew only a fraction of these writers, and several of those only by name. Most of the stories occasioned a trip to Google, where I found information and links I would not have in the couple of sentences the book itself might have contained.

The contributors are an international, multiethnic roster whose interest in Delany shows in their attention to race and gender and the pleasure they take in language. The book was funded by an Indiegogo campaign, and the publisher’s website had an open call for submissions. Somehow I doubt that Junot Diaz, Nalo Hopksinson, Kit Reed, Michael Swanwick and a few of the others answered an open call. And then there is Thomas Disch, who died in 2008. As I said above, more editorial content is badly needed, but finally that can’t take away from the enjoyment of the 30 stories and four critical essays included.

A few personal favorites, specifically from authors I did not know:

Claude Lalumiere: “Empathy Evolving as a Quantum of Eight-Dimensional Perception.” A misanthropic human time traveler finds himself millions of years in the future. Octopi are the dominant species, and if they don’t eat you they absorb you. This sets off a change of incarnations over the eons, in one of which the cephalopod/human entity may become God.

Anil Menon: “Clarity.” A professor of computer science in India finds himself living inside one of the theoretical models he and his co-workers consider thought experiments.

Geentajali Dighe: “The Last Dying Man.” According to Hinduism, the world destroys and recreates itself in cycles involving millions of years. And yet it has to happen sometime. A man and his daughter in Mumbai find themselves dealing with the day-to-day reality of the transition.

Weslyan University Press keeps in print around 1,500 pages of Delany’s critical and theoretical writing, and he prompts a fair amount of critical writing from others. There are several essays here, but Walida Imarisha’s very personal account of her engagement with both the man and his writing best conveys the significance Delany has had on writers of color. “So long seen as the lone Black voice in commercial science fiction Delany held that space for all the fantastical dreamers of color who came after him.” She goes on to propose that she and other writers become “walking science fiction…living, breathing embodiments of the most daring futures our ancestors were able to imagine.”

She is not asking anyone to sign onto her vision, but reading Stories for Chip you see that vision in action.

Book Giveaway: Babel-17 by Grand Master Samuel R. Delany

After posting about this weekend’s Damon Knight Grand Master Award ceremony yesterday we talked to the fine folks at Open Road. We decided what better way to celebrate the occasion than by hosting a giveaway? Up for grabs are 5 digital copies of Delany’s seminal work Babel-17 and all you have to do for your chance to win is re-tweet the tweet below or leave a comment here in the blog. Do both and double your chances!

After posting about this weekend’s Damon Knight Grand Master Award ceremony yesterday we talked to the fine folks at Open Road. We decided what better way to celebrate the occasion than by hosting a giveaway? Up for grabs are 5 digital copies of Delany’s seminal work Babel-17 and all you have to do for your chance to win is re-tweet the tweet below or leave a comment here in the blog. Do both and double your chances!

The contest will run until next Friday the 23rd and is open world-wide to US and Canadian residents only. Next Friday we’ll put all the names into a hat and randomly draw 5 winners. Easy peasy.

RT & win Samuel R. Delaney’s Babel-17 (ebook): http://t.co/eauYInoFdR Comment on post to double enter @OpenRoadMedia pic.twitter.com/xNTZJbtXXt

— Worlds Without End (@WWEnd) May 16, 2014

In a war-riven world, why will saving humanity require… a poet?

In a war-riven world, why will saving humanity require… a poet?

At twenty-six, Rydra Wong is the most popular poet in the five settled galaxies. Almost telepathically perceptive, she has written poems that capture the mood of mankind after two decades of savage war. Since the invasion, Earth has endured famine, plague, and cannibalism—but its greatest catastrophe will be Babel-17.

Sabotage threatens to undermine the war effort, and the military calls in Rydra. Random attacks lay waste to warships, weapons factories, and munitions dumps, and all are tied together by strings of sound, broadcast over the radio before and after each accident. In that gibberish Rydra recognizes a coherent message, with all of the beauty, persuasive power, and order that only language possesses. To save humanity, she will master this strange tongue. But the more she learns, the more she is tempted to join the other side . . .

This ebook features an illustrated biography of Samuel R. Delany including rare images from his early career.

Babel-17, winner of the Nebula Award for best novel of the year, is a fascinating tale of a famous poet bent on deciphering a secret language that is the key to the enemy’s deadly force, a task that requires she travel with a splendidly improbable crew to the site of the next attack. For the first time, Babel-17 is published as the author intended with the short novel Empire Star, the tale of Comet Jo, a simple-minded teen thrust into a complex galaxy when he’s entrusted to carry a vital message to a distant world. Spellbinding and smart, both novels are testimony to Delany’s vast and singular talent.

Our thanks to Open Road for the great contest! Check out their list of Delany titles and many other authors on their site. Good luck to everyone and please help us spread the word about the contest. Don’t forget to check back here next Friday to see if you’ve won!

Full Details

Full Details