Science fiction explores several landscapes. Outer space is the most widely known of these. Inner space has been the setting for a tiny fraction of science fiction, for example, The Dream Master (1966) by Roger Zelazny and The Lathe of Heaven (1971) by Ursula K. Le Guin. However, within my lifetime a whole new fictional territory emerged with cyberspace, the digital landscape. Neuromancer (1984) by William Gibson is usually credit with starting the cyberpunk movement which made cyberspace famous, but many digital landscape stories existed before that.

The digital landscape needs both computers and networks to exist, so it’s easy to think that science fiction about cyberspace couldn’t exist before them. However, “The Machine Stops” (1909) by E. M. Forster essentially imagines cyberspace and machine intelligence without knowing about computers, binary mathematics, or stored data. It’s not hard to give some credit to Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland as an early explorer of the digital landscape, although we could consider mathematics to be a whole landscape itself.

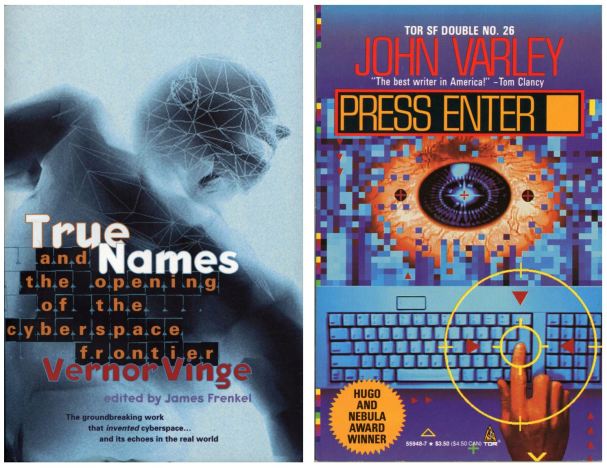

“True Names” (1981) by Vernor Vinge prefigures everything that will become cyberpunk. Sadly, it’s never been reprinted much. In 1996 it was included in David Hartwell’s Visions of Wonder, a major retrospective anthology, and in 2001 it was reprinted in True Names and the Opening of the Cyberspace Frontier edited by James Frenkel which collected many essays by famous computer scientists to introduce the story and explain why it blew their minds.

“Press Enter ▮” by John Varley came out in the May 1984 issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction, a few months before Neuromancer. That story is much more famous, winning the Hugo, Locus, and Nebula awards and being often reprinted.

Both “True Names” and “Press Enter ▮” presented science fiction readers with early visions of the digital landscape and both were horror stories about a machine intelligence emerging out of the internet. There have been so many stories about cyberspace and malevolent AI since then. It’s hard to remember these two stories are the Jules Verne and H. G. Wells tales of the subgenre. Both are available online, probably illegally, but you can read “True Names” and listen to “Press Enter ▮.”

“True Names” is the more fanciful of the two, really a fantasy story, because the protagonist, Roger Pollack (“Mr. Slippery”) enter cyberspace in a rather unbelievable way. Roger and his partner Debbie Charteris (“Erythrina”) paste sensors to their skulls and go into a trance to traverse the digital landscape using fantasy motifs of warlocks and magical powers. Vernor Vinge asks his readers to believe they can experience massive amounts of data in cyberspace as a form of expanded consciousness. It’s really just a fantasy portal no more realistic than C. S. Lewis’ back of a wardrobe. It’s an exciting story and moves extremely fast for being a novella, but unfortunately, neither Roger or Debbie are deeply developed as real humans or as their hacker alter egos Mr. Slippery and Erythrina. However, I was moved by the scene when we get to see who Debbie is as a real person.

“Press Enter ▮” is far more realistic. Victor Apfel is a character of complexity. He is a semi-invalid Korean war vet living next to Charles Kluge, a master hacker. Kluge commits suicide and tricks Victor into discovering his body. The police hire Lisa Foo, another master hacker to process Kluge’s house full of computers and software. Victor and Lisa become friends, then lovers. Lisa is a Vietnam refuge, so she and Victor have a complex shared background with several Asian countries.

Neither Kluge or Lisa enter cyberspace, both just sit at terminals hours on end. They live in this reality and the cyber landscape can only be deciphered by data dredged from computer screens. This makes the horror of an emerging AI intelligence far scarier, and the ending particularly vivid.

I reread these two stories yesterday because I’m working on a list of my 35 favorite science fiction short stories. Piet Nel suggested limiting ourselves 35 stories because if they were published as a book it would be about the size as one of Gardner Dozois’ big anthologies. That means I’m going to have to leave out a lot of fondly remembered tales. I’ll have to decide between “True Names” and “Press Enter ▮” – because of their overlapping themes. I suppose I could argue back with Piet that we should consider 109 the limit. Jeff and Ann VanderMeer’s The Big Book of Science Fiction proves it is possible to go truly gigantic with an anthology.

In the end, I’ve decided to use “Press Enter ▮” for my list. “True Names” was more colorful and fantastic. But I have to consider it cyberfantasy, rather than cyber-SF. More than that, I envisioned Victor and Lisa way more than I could with Roger and Debbie.

Comparing the two stories helped me with my problem of picking favorite stories. As I’ve been going over the SF stories I love most and rereading them, I’ve discovered certain aspects inherent in stories are what makes me like them. These qualities are hard to label. All fiction must hook us, must contain a thread of suspense to keep us reading. I’ve been trying to identify those elements within a story that hooks me and keep me reading. Here’s what I’ve got so far:

- The main character has to feel real. In fact, the more real the better. I have to identify with the character, even if I don’t like them. Stories that feel like I’m reading about a person experiencing a real event, even if I know it’s fictional or fantasy, is what grabs me most.

- The subject matter is next in importance. I can read a masterpiece of fiction about any subject, and admire it tremendously, but I only develop a psychic love affair with stories that involve my life-long pet topics.

- The story needs to explore philosophical problems I want to understand. I love stories the most that give me philosophical/spiritual/personal insight.

I’ve also learned there are elements in stories that make me want to stop reading.

- I’m turned off by prose that calls attention to the writer. I don’t want to be reminded that I’ve entered fiction-space.

- I don’t like artificial constructs. I know writers love to play around with how they tell a story, but if it jars my attention that detracts from my reading pleasure.

- Unbelievability is a reading buzzkill. I know when I reading the literature of the fantastic, but even it has to have a feel of believability.

Cyberspace and artificial reality are concepts that have emerged in our lifetime. We’ve watched writers work to make them believable, to create portals into this new digital landscape. The most realistic stories are those where humans wear goggles and suits. It is quite popular now to have stories where brains are recorded and people’s minds are transferred into artificial realities. I don’t accept brain downloading. I can accept it as a fantasy portal, but not as science fictional speculation.

We use to say the universe was everything, but now with multiple universes becoming accepted, I call the whole enchilada reality. Earth, outer space, inner space, and the digital landscape are all part of a single reality. Both inner space and digital space must be explained by the laws of reality.

Fiction space can work outside the laws of reality. However, I prefer stories that do.

I prefer “Press Enter ▮” to “True Names” because it confirms more with reality. But I also resonate better with the John Varley story because Victor and Lisa are compelling characters that come with realistically detailed biographies. Both stories deal with the same philosophical problem though — the threat of computer intelligence. And even here, I give the nod to Varley. Not that Vinge hasn’t created a powerful imaginative story, I just resonate better with Varley’s realism. I imagine other readers will prefer Vinge because his cyberspace is more colorful, and they accept that fiction space can work outside those laws of reality.

JWH

Hi Jim

Interesting I will have to track down the Varley story. I read the Vinge story because it was discussed as one of the important stories in the history of cyberpunk. But as you suggested I found it more cyberfantasy, a bit like the work of Piers Anthony where stories that are supposed to be SF enter some metaphor heavy place and we are suddenly dealing with archetypes and vague bits of magical hand waving.

Happy Reading

Guy

LikeLike

I haven’t reread either in a long time, but my impression is that “True Names” was better. I think because bits of “Press Enter#” rubbed me the wrong way, especially the male fantasy love story aspect.

Anyway the great underappreciated Vinge novella from that period is “The Blabber”, set in a beta version of his Zones of Thought universe, and an utterly amazing story. Sense of wonder out the wazoo!

LikeLike

I was expecting to like “True Names” better from lingering memories and its legendary status, but “Press Enter _” wowed me this time around. I thought the love story was realistic. Both stories are genre classics and should be read and remembered.

I’ll track down a copy of “The Blabber.”

LikeLike

Love Vernor Vinge, but I totally agree. Just read Press Enter in 2022. Completely terrifying, great characters and a believable love story. Haunting and convincing. Barley’s AI is exactly what too many of us have nightmares about; unknowable and godlike but uninterested in humanity, only in it’s parasitic continued existence.

LikeLike